An important aspect of running great STEM challenges is you! Your teaching philosophy probably already leans away from “sage on the stage” if you’re drawn to using STEM challenges, but facilitating takes practice, reflection, and more practice!

Ever caught yourself wondering if you’re running your STEM challenges well? Below you’ll find my “DOs and DON’Ts” for preparing for and running a great challenge. The video offers full details, and there is a written summary below.

However, if you prefer to read, you’ll find the video transcribed at the end of this post.

Your Role as Facilitator, part 1:

Summarized thoughts:

Prep

– Choose a challenge

– Set your group size

– Set your criteria & constraints

– Plan for two iterations & possibly extension activities (more on this in part 2)

– Create your own design ahead of time to help develop criteria & constraints and materials ideas, if time permits

– Have students help you set up materials ahead of time for speedy distribution

During the Challenge

As always, reach out in the comments or by email if there’s a specific question or topic you’d like me to address. 🙂

Credits:

Video Transcription

your role as the facilitator during STEM challenges, and I’m going to break it

into two parts. The first part this week will cover how you prepare for a STEM

challenge and then what you’re actually doing while the students are building,

and then next week I’ll post part two, and that will cover everything that

happens once the build phase is done, what comes next. So, if you’ve had kind

of a nagging feeling that you’re not quite getting everything you could be getting

out of STEM design challenges, then hopefully this video will help you get a

little bit more juice for the squeeze.

you’ve already watched the five keys to STEM challenge success that I posted

last week, and if you haven’t, stop and watch that now. I’ll either link it in

the video somewhere, or in the description below. Go back and watch that first.

So, you’ve selected a challenge, you’ve set your group size, you’ve decided

what your criteria and constraints list will be, and you’ve put in your plan

book how much time you need. It’ll probably be 75 to 90 minutes if you are new

to STEM challenges, and if you’re more experienced or you’ve chosen a more

simple challenge, you could probably get it done in an hour, but I tend to like

to plan a little bit more time, more wiggle room so you can really take

advantage of some of the discussion and extension activities.

the luxury of time, and I know as a teacher you don’t have a whole lot of it,

but whenever you can, do the STEM challenge ahead of time yourself. One of the

things that really helps me to do is figure out where the frustrations will

lie, where I might have some problems with materials. Sometimes I think,

“Oh, you know what would really be great is if I had just paper

clips,” and so I can throw that in, and also just ideas as to what to add

to criteria and constraints list. So, I know that might not be practical with

every challenge, but if you can, I highly recommend it. Also, it’s a fun

activity to do with your friends or your family. It can be a little competitive

as adults, but it’s a lot of fun. I enjoy it.

challenge, you have a lot of materials to distribute. One thing that’s very

helpful to do is the day prior, or if you have a lunch period that’s prior to

when you’re going to build, to invite a few students in to help distribute the

materials into paper bags or bins so that it’s a quick start to the challenge.

You can just pass out the bins or the bags. If you have parent volunteers, same

sort of thing, and if not, you can just have, from each group, have the

students divide up who’s going to go pick up the pipe cleaners versus the

popsicle sticks versus whatever else so that that will go quickly as well.

students and its time for them to get started, there are different approaches

to planning, and this is a great place for you to differentiate. So, some

people like to sketch out their idea first; some people like quiet time to just

think about what they might want to do; some people like to discuss it in a

group and then start building, and some people, and I would count myself in

this, just want to start putting your hands on the materials to sort of start

playing with them and test some ideas out. Now, it’s probable that your

students don’t know which type they are, and so I would recommend varying it

and trying different planning methods with different iterations and different

challenges to help students see the different approaches and what really works

well for them.

you stick with one approach, let’s say you do the sketch before you build, that

would be difficult for me. I can’t draw anything, and I get really frustrated

and annoyed when I have to draw something. Not that that means I should never,

ever try it, but if that’s the only way I’m allowed to plan, and I can’t start

building any other way if I don’t have a picture drawn, I’m going to be really

annoyed and frustrated as I get into the challenge, and that’s just not

something you want. So, I would recommend trying in different ways,

differentiate it for your different learners, and help the students figure out

what is the planning method that works best for them.

your game face on, and you’ve got to remember that this is about the growth of

the students in their problem solving skills and their resilience, and you

might need to have a mantra in your mind in order to make that work for you.

So, sometimes I go about thinking failure is fabulous, or facilitate, don’t

fix, or let them fail and let them recover. I don’t say it out loud, but I say

it in my mind sometimes when I want to get my hands in on something that

they’re doing, and for some people that’s not an issue at all, but for people

who got into the teaching profession, it’s often because you want to help, and

we just have to remember that it’s not helpful to stunt their growth and their

ability to help themselves. So, this is something I have to tell myself a lot,

and I said the last video, but I will repeat it, I will cross my hands so I

don’t touch their activities or their designs, and sometimes I cross behind my

back as well, just as a physical reminder that it’s their design and it’s their

challenge.

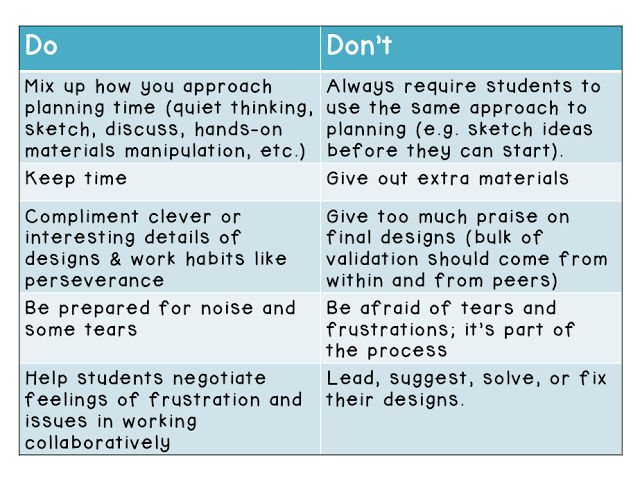

do, and what don’t you do? As I mentioned last time, one of the things you can

and probably should be doing is calling out a lapsed time so students know how

much time has passed and how much time they have left to build. Again, you can

have someone in a student group do that, that’s a personal preference. I prefer

not to do it that way. One thing you don’t do is you don’t give them extra

materials. Materials are constrained for a reason, so when students use their

entire length of masking tape and they say, “Oh, but we used it all. Can I

please, pretty please have some more?” The answer’s no. You don’t have to

be mean about it or rude about it, just say, “Oh, I’m so sorry. That’s one

of the constraints, so now you have to try to figure out a way around it and

how can you work without having the tape.”

students, and maybe some rolled eyes or a deep sigh, depending on how old they

are, but they do get over it and they frequently do find a way around it. If

they don’t find a way around it, well, then the next time they do their

iteration, they’re a lot more careful about the way they use the materials.

That’s an important lesson to learn.

you say as you walk around the groups to see what they’re building? Well, one

of the things I like to just start with every group is tell me about your

design, or tell me what you’re building. Then I have some examples of some

other questions that I’ll ask as I’m going around, so let’s just take a look at

those. Basically, the key to the questioning is not to be too leading or give

your own suggestions. You don’t want to inadvertently teach students that when

they get to a tricky spot they just have to wait on you to show up and solve

it. Engage the students in conversation about their designs, and help talk them

through their problems so they can determine their own next steps.

out before you leave, either. Just be interested and be as perplexed as they

are by the problem, encourage them to keep at it, and tell them you’ll check

back again in a few minutes. Then you just go off to the next group and do it

again. Some students might need a little more support than others. You’ll

noticed I starred the first don’t say here. This amount of scaffolding could be

appropriate in some cases, but in general, it’s too leading. You have to use

your own judgment based on what you know about your students. Just be careful

that you keep pulling back the amount of scaffolding you provide so the

students become more self-reliant over time.

of failed designs. I like to point out some of the more happy failures of

engineering, like post-it notes and microwaves. I’ll link to a site to those

and others in the description below. There are many inspirational quotes on the

topic that you can share as well. I’m going to talk more about that next week.

Finally, you might disagree with me here, but I try not to be too effusive with

my praise of student designs. That’s not to say I don’t compliment. I do. I

like to point out something clever or interesting about all the designs, or

even the ideas that perhaps didn’t execute as planned in the designs. I just

try to be very even in my tone, almost observational, and always choose just a

detail of the work or a habit, like perseverance. I like to leave the big compliments

to their peers. Long story shorter, I don’t want them seeking my validation. I

want the working with a clear mind on designs they think are cool, not on

something they think I’ll think is cool.

as you go around, you want to be prepared for a couple of things. First of all,

STEM design challenges do tend to be on the louder side. Students are working

in groups, they’re very excited about what they’re doing, and they’re under a

time constraint. If that’s the kind of thing that bothers you, the noise level

getting too high, before you start the challenge, you need to make sure you set

with the students some sort of signal for the noise getting too loud, if it’s

flashing the lights or whatever, so that they can bring it back down to a

reasonable level.

especially if you have younger students, is there could be tears. Students

sometimes do get frustrated to the point of tears, and that’s not necessarily a

terrible thing. I know I’ve been frustrated to the point of tears before, and

it’s one of the things that you just have to learn to get over and to get past.

So, when this happens to students, I don’t try to tell them that they shouldn’t

be crying, or anything like that. I do sort of come over and commiserate with

them and just say, “I know these things can be really frustrating,”

and I usually try to give them an example of … Especially if I’ve done the

challenge ahead of time, then I can sort of say, “Oh, when I was building

my tower, the air conditioning kept blowing it over and I was so annoyed that I

just had to walk away.”

they do get that frustrated that they’re crying or they’re just really angry,

try to give them some ideas for how to handle that, like, “When I get to

that point, sometimes it helps me to focus on a different aspect of the design

challenge, or a different aspect of the problem for a while and just give

myself a brain break, or sometimes I have to walk away for a second. Go to the

water fountain and get a drink, come back.” Just that sort of break, that

physical break with what they’re doing can be helpful. Just let them know

that’s a perfectly human emotion to be frustrated when something’s not working

the way they want it to. But don’t be fearful of tears.

recommend is whether the students are frustrated with how the design is going,

or frustrated with their teammates, one of the things that I do is I try to

talk them through a little bit of those aspects, and then I’ll just tell them,

“Keep working on it. I’m going to come back and check in with you guys

later.” And I go around to some of the other groups, and I would say nine

times out of ten, by the time I make it back to that group, they’ve figured out

a solution to their problem. So, you just have to give them the time and the

space. Take a step back, let them figure it out, almost always they will.

STEM challenge and then what to do during the STEM challenge. Get excited.

You’re going to do great. You’re also not going to do great, and that’s okay.

We have a growth mindset for the students and for ourselves here. Even when I

do STEM challenges now, always, when I’m walking away from it, I think,

“You know, in this interaction with this student, I maybe helped them too

much, or maybe I led them a little too much with my questions and the way that

I asked them.”

to be perfect, but you just got to keep trying it. Every time you’re going to

get a little bit better, and you’re going to feel a little bit more confident

in your ability to let them develop their own abilities. You just got to give

it a little bit of time, and remember, perfect is the enemy of good. Don’t get

yourself all beat up about it, just keep going forward, just keep trying them.

It gets better and better and better, and next week we’ll talk about what you

do after the challenge.