I started my career teaching 5th grade in 2000. Any classroom teacher will tell you that first year is a killer. Hanging on for dear life, I decided not to pursue a master’s degree, or in fact any hobbies or social life outside of teaching; there simply wasn’t time.

Fast-forward to 2008: Since I kept coming back to the classroom each fall, it seemed silly to do it for less pay than I had to, so I decided to look for a master’s program. My peers suggested I choose something online and just “get it out of the way,” but I couldn’t commit to what appeared to be a miserable slog. Then I discovered Design-Based Learning (DBL).

While I had always gravitated to hands-on engaging activities, this master’s program completely changed my approach to teaching. In short, all the members of this K-12 cohort of teachers created a year-long curriculum in which a series of interrelated design challenges served as the context for cross-curricular, standards-based lessons that followed. (I know that’s a bit of a mouthful!)

Translation: I created the Planetopia project. The premise was that in the year 2035, Earth had run out of room. The students were tasked to find a new, Earth-like planet (Planetopia) to colonize. in which my students completed challenges to create landforms, cities, creatures, plants, modes of transportation, etc. over the course of the school year. (I used this premise as the basis for my Earth Day STEM Challenge.)

What you see in the image below on the table is my second-grade class’s Planetopia land parcels. On the black bulletin board are some of their creatures and work related to the challenges. The post-it note posters above show one poster for every challenge and the subjects and standards-based lessons connected to each challenge.

Why I (Still) Love DBL

There are many reasons I loved using DBL in with my classes. From a planning perspective, the framework of the challenges could be used in any grade level by using the content standards as inspiration to tweak the challenge criteria. I did the Planetopia project with 2nd, 5th, and 6th grade classes. Teachers in my cohort created similar frameworks for K – 12.

My students loved the challenges and it made them innately more interested in the content I needed to teach when I could relate the lessons back to something they built with their hands.

But what it really boiled down to is DBL helped me find the joy in teaching again. Facilitating these challenges, seeing the students light up as they solved their own problems, giving students who weren’t successful with traditional paper/pencil tasks a stage to shine upon and impress their peers…nothing can really compare to that in my book.

From DBL to STEM Challenges

DBL can be a little intimidating because it involves making a year-long, synced curriculum; most classroom teachers don’t have time for that! STEM Challenges offer many of the same benefits of DBL in bite-size pieces. (Read my guest post for more on the benefits of STEM Challenges.) While you lose some of the benefits you get from the continuity and inter-connected nature of DBL, you gain some flexibility and practicality with STEM Challenges, opening you up to more challenge possibilities and, of course, saving some prep time. Score!

The STEM challenges I create are informed by my study of DBL, in an attempt to get as much bang for the instructional buck as possible! For example, even though they are STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) challenges, you’ll almost always find activities/lessons for additional subject areas in my extension suggestions; I can’t help myself.

I also stray from the traditional engineering design process, in favor of a DBL tenet: students design and build BEFORE they research. This is crucial for a couple of reasons. If they build first, the result is more innovative designs, and it gives students a reason to want to research and do follow-up lessons. They want to know how to make their designs even better — or why their designs didn’t work — so they are innately more interested in the content.

I also stray from the traditional engineering design process, in favor of a DBL tenet: students design and build BEFORE they research. This is crucial for a couple of reasons. If they build first, the result is more innovative designs, and it gives students a reason to want to research and do follow-up lessons. They want to know how to make their designs even better — or why their designs didn’t work — so they are innately more interested in the content.

On the flip-side, when you have students research first, their designs tend to replicate what they have seen. And since the students will all have seen the same, or at least similar, images, all the class designs are more likely to turn out stamped from that cookie-cutter.

I choose the DBL approach: First iteration of the challenge; followed by lessons and research; followed by a second iteration or modification of the first design. I know you won’t always have time to do it this way, but definitely try to make it happen as often as possible. You won’t be sorry!

STEM Challenges: Get your Groove Back

If you’ve been feeling like you’ve lost your inspiration, STEM Challenges might help you get your groove back! It helped me remember why I wanted to teach and what kind of teacher I wanted to be.

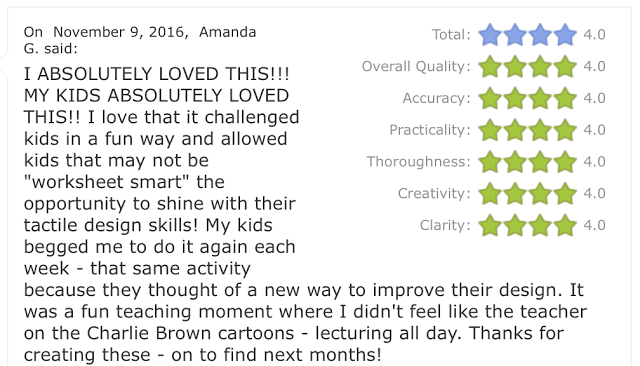

I have been so heartened and encouraged by the feedback I have been seeing from teachers experiencing the same influx of joy into their classrooms.

My all-time favorite feedback on a STEM challenge resource says it best:

|

| Feedback from the Halloween STEM Challenge Bundle |